A Friendship. A Local Legend. And the Battle Of A Lifetime.

"He cannot write anymore — a crime for a man who has so many interesting things to say. I think that’s why I understood the extra meaning he intended in two words he spoke that I will never forget."

I did not cry after I said goodbye to my friend, but as I drove away from his house and headed toward the freeway that leads out of Fresno, I could feel my heart clench. Then I noticed my hands were clenched tightly to the top of the wheel. All I could think about was how monstrously cruel a disease like Parkinson’s can be. And what a very good man my friend is.

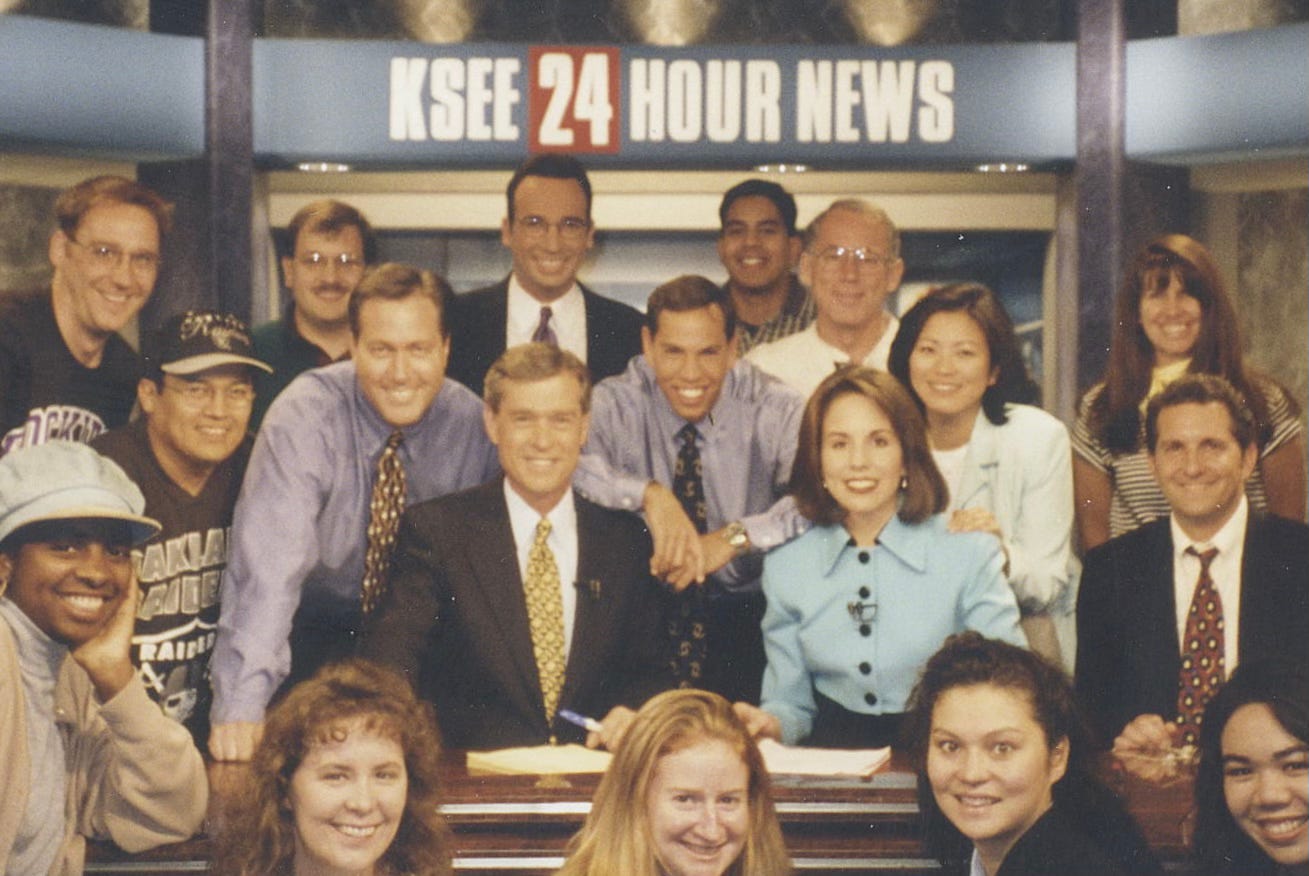

I first met Bud Elliott 29 years ago on my first day at KSEE-TV, the NBC affiliate in California’s sprawling Central Valley. We were in adjacent cubicles, inches apart and at eye level. We could hardly have been more different: He was a 30-year veteran news anchor, I was the young reporter still hungry to learn. He was a conservative, I was a liberal. He, a good Christian. Me, a proud Jew. Bud was reserved in his speech and had a killer dry wit. I talk a lot, and you’d hardly describe my sense of humor as clever.

But for some reason, Bud and I clicked in a snap. He liked my writing and he didn’t mind answering my myriad questions about, well, everything. This includes all the times when I said: “Buddy, just one more question” (usually followed by another question).

Bud Elliott was born in Plentywood, Montana, and grew up in Albuquerque, New Mexico. He was already working as a DJ on AM radio before he went off to college at Colorado State University. By the time he’d left the Centennial State 10 years later, he had worked in roles as an anchor or news director at more than a dozen radio and TV stations — often two jobs at once.

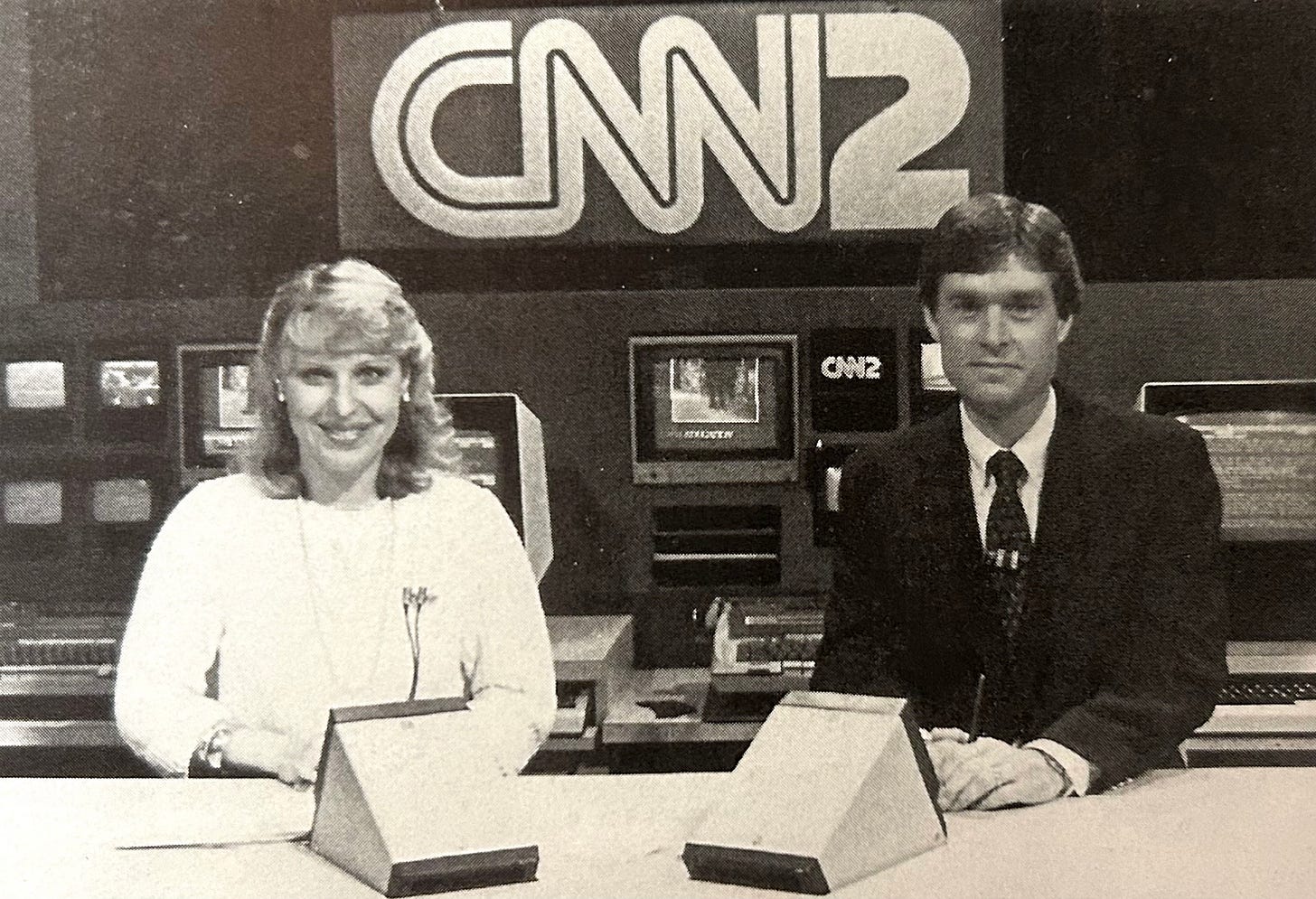

In 1981, Bud Elliott became one of the first anchors to appear on CNN’s Headline News. Pretty cool. But he missed local news, and it led him back to cities like Denver, Jacksonville, and Richmond, Virginia. In 1987, Bud settled down in Fresno, the city and community he would become a local institution in for the next 35 years.

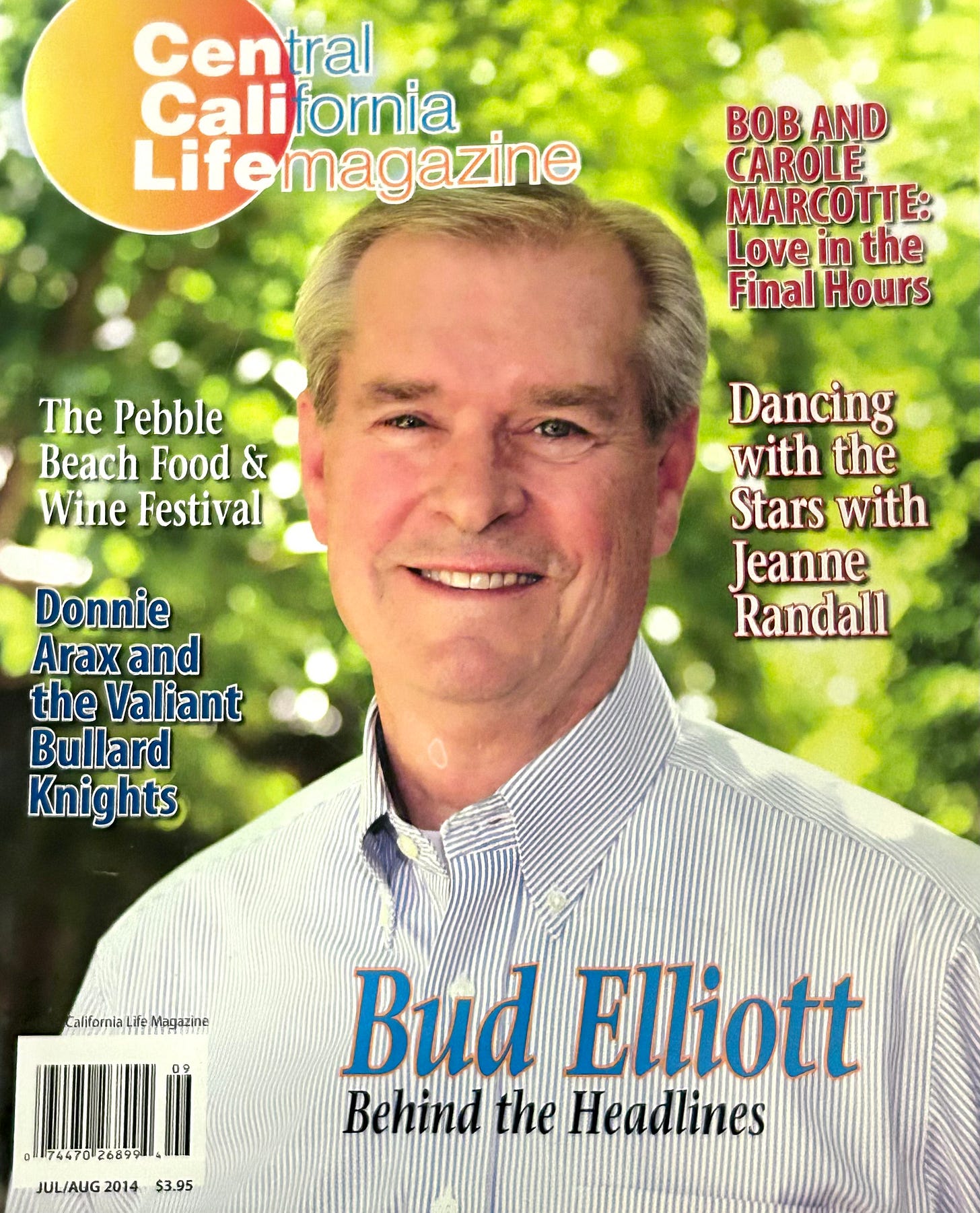

Fresno is the 53rd ranked TV market by population, just larger than the city of Buffalo and slightly smaller than New Orleans. Because it’s the main TV station in the San Joaquin Valley, journalists cover a ton of news stories that break between L.A. and the Bay: Forest fires, draughts, agricultural crises, rock slides in Yosemite, life-threatening temperatures in the Valley, as well as a perennial gang problem, persistent violent crime — and no shortage of murder trials. Also, a ton of political corruption. For 24 years, Bud covered it all with grace and integrity, earning countless awards for his work. Throw in all of the charity events he hosted and PBS drives he appeared on, and what you get is a lasting legacy. (Here's dapper Bud back in the day).

The single most memorable day I had working with Bud came in 1996, when the Clinton-Gore reelection campaign swung through Fresno. Our boss had tapped the two of us to do live shots throughout the day at a huge rally the campaign was holding at Dailey Elementary School.

Keep in mind, Bud was the consummate pro, and while I’d covered my fair share of local politics, I was the puppy dog who was thrilled to be covering a presidential visit. I think I got to Dailey at least half an hour early in my best tie and sports jacket. When Bud finally arrived, I bum-rushed him and fired about five consecutive questions without a breath. I will never forget his reaction. After calmly absorbing my nervous energy, Bud placed his hands on my shoulders, looked me straight in the eye and said in a lilting voice: “Mikeeeeee, relax. Breathe. It’s a loooong day.”

We both busted out laughing. And we’ve been calling each other Buddee and Mikeeee ever since.

I left KSEE-TV just before 2000, returning to Chicago and a new career working inside the political world. I would visit my old friends in Fresno a few times in the intervening years, but Bud and I kept in regular touch. He picked up the screenwriting bug, and he would let me read his scripts. He was good. Likewise, he’d buy my books and always encouraged my writing. Even when it became too hard for him to talk by phone last year, he sent me a terrific book on Israel for Hanukkah. It wasn’t easy to read the cursive on the card, but when I saw the “Mikeeeeeeeeeee” that he intentionally continued onto the back page, I laughed out loud.

In 2013, Bud noticed what he thought might be the earliest symptoms of Parkinson’s. Tests confirmed it. A year later, though the symptoms were not advanced, he stepped down from NBC. He just didn’t feel he could be the same kind of journalist and leader in the newsroom that he had always been. Doing things half-ass was never his style.

In retirement, Bud has been able to spend more time with his heroic wife, Peggy, their two kids, and soon enough, a grandchild. He took up woodturning as a hobby, quickly excelling at it. And he became an advocate for Parkinson’s fundraising and research projects. For 10 years, he has been especially active in the Rock Steady Boxing program.

I recently drove to Fresno to visit Buddy and Peggy. She now takes care of him full-time at home, as he is in Stage 5 of Parkinson’s. It is extraordinarily hard — for both of them.

During our visit, Peggy and I did most of the talking. Bud is still sharp in mind, but it’s very hard for him to speak and be heard. As we ate lunch in the kitchen where I’d spent holidays so many years ago, I obtusely asked Bud if in any way he has been able to get used to the symptoms. I leaned in to hear his wise and kind answer:

“You never get used to it. You just come to terms with it.”

There are 90,000 new cases of Parkinson’s Disease every year in the U.S. It is a progressive neurological disorder that carries symptoms that can include tremors, slowness of movements, trouble walking, trouble sleeping, depression and speech problems.

For countless families and loved ones who deal with Parkinson’s daily, and especially for caregivers like Peggy, it is indescribably frustrating that no cure has been found (for elected officials and well-heeled donors who want to have a real impact on this sick riddle, I urge you to support Lou Weisbach’s brilliant concept of the American Center for Cures).

At 75 years of age and after more than a decade living with Parkinson’s, Bud is battling every day. It’s not easy for him to entertain visitors, so I was thrilled that he wanted me to come to Fresno. And even though I did most of the talking, I knew he understood every word — and had a hilarious comeback in his head for at least half of my jokes. Even without hearing them, I could hear them.

Before I left, I gave my friend two gifts: 1) a pair of socks that said “Studies Show I’m The Shit,” and, 2) a framed photo of us together at that presidential campaign event. He instantly wanted to go into his office and create a spot for it on the wall. I treasured it on my own wall for years, yet I could not have been happier to give it to him.

In the few hours we spent together, Buddy probably spoke fewer than 100 words. He cannot write anymore, which is a crime for a man who has so many interesting things to say. I think that’s why I understood the extra meaning he most certainly intended in two words he spoke that I will never forget:

“Keep writing.”