Becoming the Best in the World

"Sadly, my Dad was working the exhibition floor when I made my 9 out of 10 to tie the king. Ever since I was a kid, I would hear Dad go nuts when he watched basketball players on TV miss free throws."

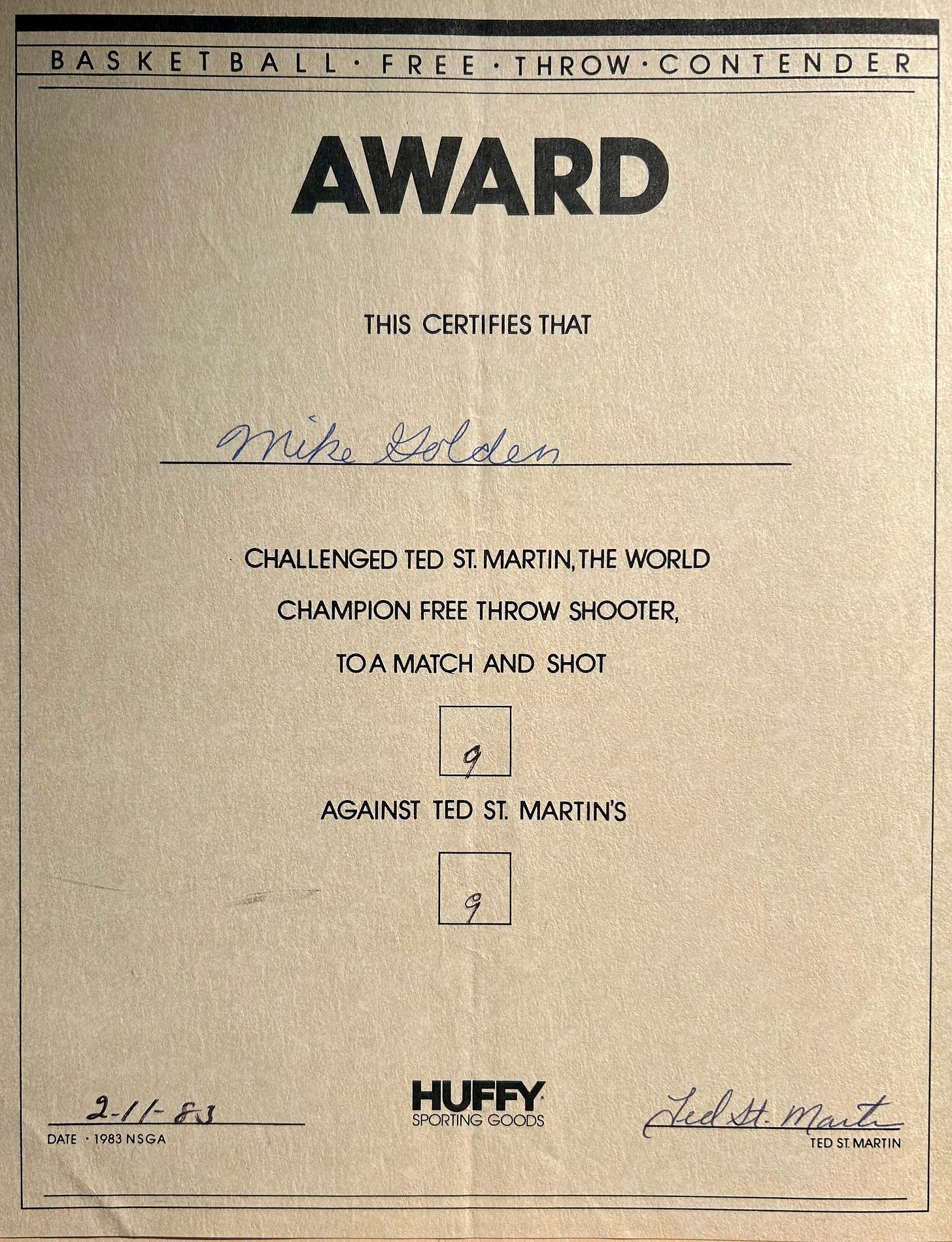

When I was 16 years old, I tied the Guinness Book of World Records free-throw shooter in a one-on-one shootout. I’m serious. I missed one out of 10, and so did he. I got lucky.

It happened at the National Sporting Goods Convention in 1983. My father co-owned a sports apparel company, and when he exhibited at the convention, he’d get two extra badges for me and a friend. Professional athletes from every sport were spread across four floors, signing photos and souvenirs as they represented every sporting goods company on the planet. It was Xanadu.

Ted St. Martin wasn’t exactly an athlete. He didn’t play pro or even college basketball. He would just shoot around as a kid. Like millions of us. He had good touch, but he was 5’7” and didn’t have a ton of vertical leap. I can relate.

But in 1996, at the age of 61, Ted St. Martin made 5,221 consecutive free throws — breaking his previous world record of 2,036.

If you watch or play basketball, Ted’s feats are sort of astonishing on a level that defy description. But they didn’t just happen. No true excellence just happens.

Ted grew up on a farm in Yakima, Washington with seven brothers and five sisters. His high school basketball coach taught all his players to shoot underhanded. He took to the Rick Barry-style shot, and kept at it.

Soon Ted moved to California to work on another farm. He played in City League games, and got better and better at making the charity shot. He posted a hoop to the dairy farm on the property, and just kept shooting.

In 1972, he set his first world record of 200 makes in a row, beating the prior total of 144. Then he kept on going, with streaks of 305, 315, 386, 927, 1,238, and then the two big ones.

Becoming the best at one single task changed Ted St. Martin’s entire life. He was hired to perform at clinics and halftime shows. Adidas, Asics and Huffy became sponsors of his exhibitions. Then Coors beer backed him, coming up with the moniker “The Silver Bullet Sharpshooter.” They bought him a traveling van, and he and his wife Barbara would crisscross the country, logging thousands of miles and free throws.

I didn’t know Ted St. Martin would be at the NSGA show that day. I didn’t even know who he was. I just got in line behind others who were waiting to challenge the champ.

Sadly, my Dad was working on the exhibition floor when I made my nine out of 10 to tie the king. Ever since I was a kid, I would hear Dad go nuts when he watched basketball players on TV miss free throws. Partly because he was a great shooter, and partly because he had bets on the games.

I got some of my Dad’s hand-eye coordination, so I was a fair shooter and then putter when I got into golf. The times when my Dad and I won golf tournaments as a team or the annual father-son basketball shoot were thrilling. During the latter, Dad wouldn’t even take a practice shot. He’d just strut up to the line, bounce the ball twice, and start. And he never made less than eight out of 10 (we still go out to the rusty hoop in his driveway about once a year, draw a free throw line, and start gambling against each other).

I didn’t realize it when Ted and I met that day back in my youth, but his whole career was a lesson in dedication and focus. This man who was an average basketball player with good hands decided he would become the best at one thing. The best in the world. And then he worked toward it with single-minded determination. The boy farmer from Yakima literally willed a whole different life for himself.

A part of me wishes that I had more of Ted’s long-term focus in my own career. For the first 25 years, I moved from field to field. I started in broadcast news, then political strategy, then worked in college scholarships before cofounding a journalism tech startup. I loved doing all of these things, and was maybe even good at a few — but none of them did I master. I moved on too early.

For the last 10 years, I have been writing and speaking as an opinion journalist. The written word was actually the backbone of most of the work I’d done in the past, so it’s a natural place to be at now. And I may have finally learned the lesson of Ted: Just keep trying to get better. Don’t get discouraged or distracted. No one else but you controls your success.

I’m glad to say that my fourth book came out last month. It’s a good feeling. But I am under no illusion that I am near the writer that I might become. And the challenge of getting better is what keeps the torch burning.

For some reason, this story about Ted popped into my head last night, and I went hunting for the certificate he signed over 40 years ago. I have albums full of autographs from the greatest athletes of the 70s and 80s. But none of them are like Ted’s.

Ted St Martin is still alive! Your wrong! He is 90yrs old!

My dad went to Yale in the 1950's. His roommate's dad was Dean of Yale Law. Dad's roommate invited him to dinner at their fancy house. At the right time the Dean looked at Dad and said, "Try in your life to be excellent at SOMETHING." I think that's good advice. The excellent thing can be anything, but being excellent at that thing establishes a special facet of one's identity.