How the Superman of Sports Shattered His Kryptonite

"The ultimate irony of Bo Jackson’s early speech struggles just might be how his strategy of substituting 'Bo' for 'I' ultimately contributed to his status as a folk hero in the world of sports."

Sometimes, when the amount of bad news in the world feels like it’s just too much, I reflexively want to write something I find fun and inspiring. So here’s a little story about a legendary athlete named Vincent Edward Jackson. You might know him as “Bo.”

Actually, even Bo used to refer to himself as “Bo.” But it wasn’t because he was doing the lame third person thing. It’s because he had a stuttering problem. The word “Bo” didn’t trip him up nearly as badly as the word “I.”

By way of background, especially for younger readers, there was a short period of time around 1990 when Bo Jackson’s name was as big or bigger than Michael Jordan’s. It’s true.

But growing up, Bo’s story was eerily similar to a well known fictional character: Forrest Gump. They both grew up in small towns in Alabama. They both had speaking disabilities. They were both perceived as stupid and mercilessly teased by other kids. And they both realized they could outrun all of those variables — literally.

One difference is that Forrest Gump went to play football for the University of Alabama, while Bo went to intrastate rival Auburn University. He also played baseball there. Oh, and competed in track and field.

The college thing almost didn’t happen at all. In 1982, at the age of 18, Bo was drafted out of high school to play for the storied New York Yankees franchise Eventually he would play major league baseball in Kansas City, Chicago and Los Angeles. His very first big league home run for the Royals was measured at 475 feet, one of the longest ever hit in Kauffman Stadium.

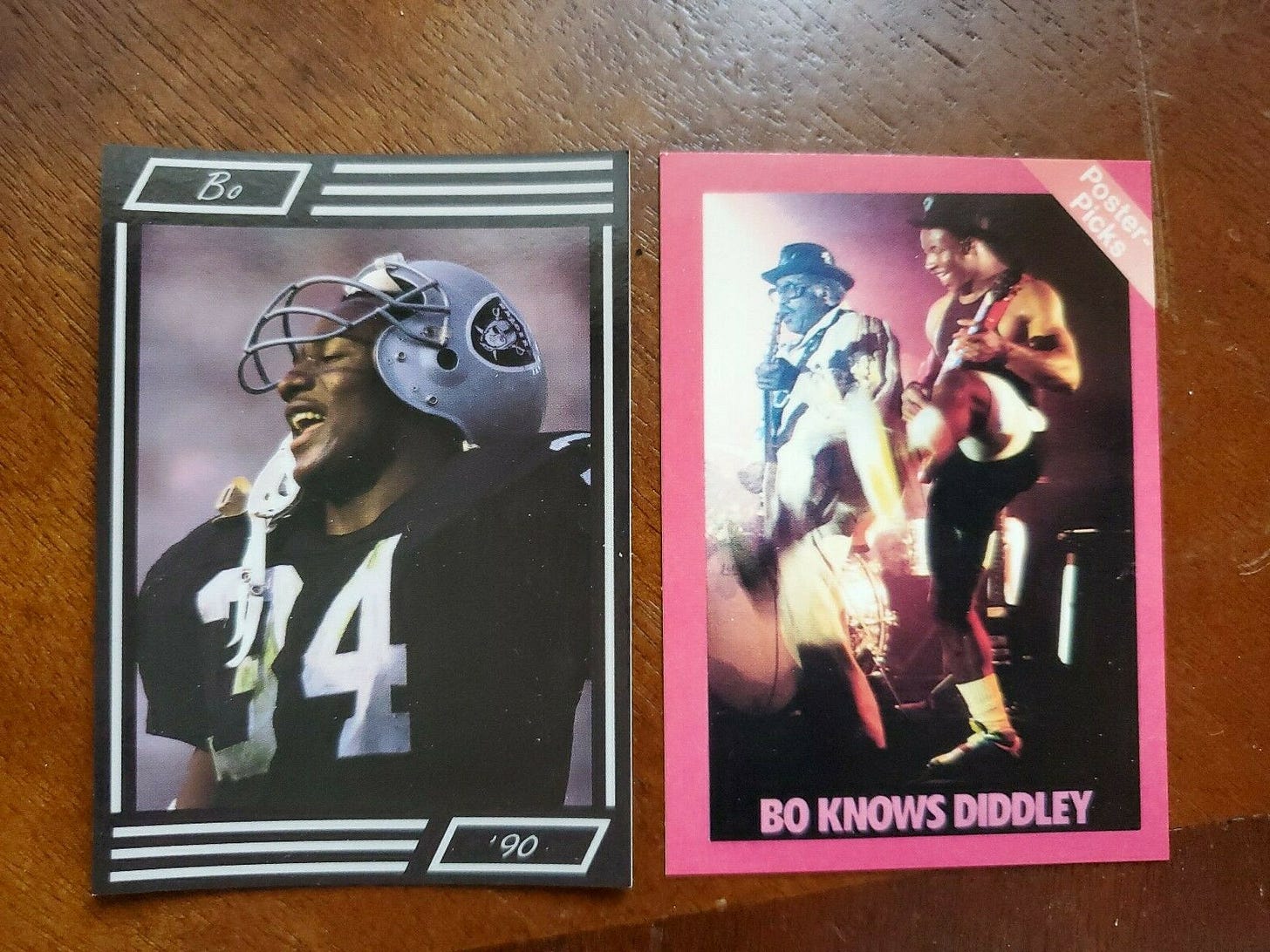

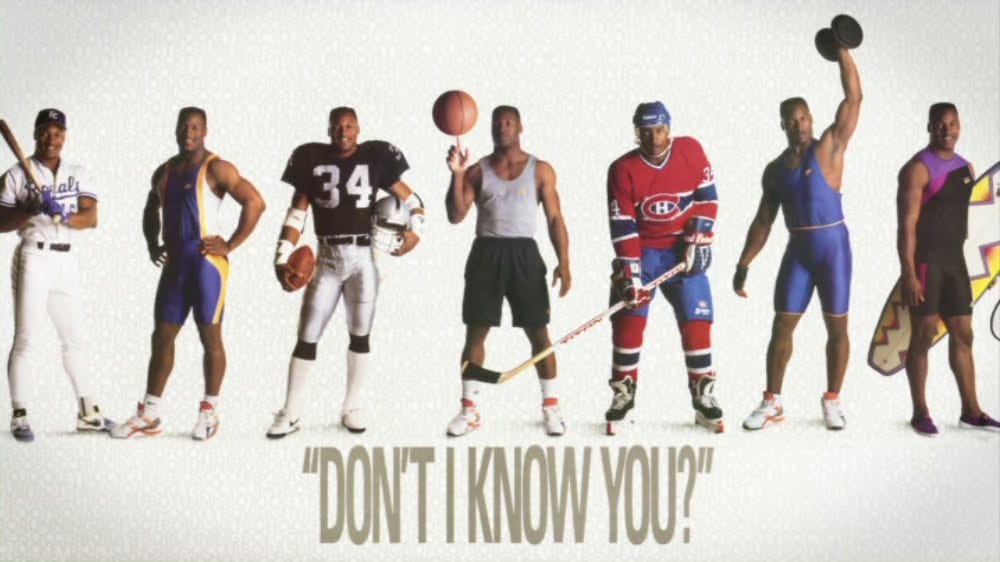

Jackson also played running back for the L.A. Raiders, and he was the first pro athlete to become an all-star in both the NFL and MLB. His freakish athletic versatility spawned one of the most famous sports ad campaigns in TV history in 1989: “Bo Knows.”

In one of the spots, which is still my favorite ad of all time, Nike took its biggest endorsement stars (Wayne Gretzky, Michael Jordan, John McEnroe, Kirk Gibson, Jim Everett, etc.) and featured each of them saying “Bo Knows (their sport).” Blues guitarist Bo Diddley plays guitar throughout the ad, and then at the end Jackson straps on an ax and clumsily plays alongside him. Magic. Nike sold a ton of their new “cross-trainers.” They even came out with new ones a year ago in Raiders’ colors.

But back to that college thing. Bo had promised his mother that he would be the first in their family to ever earn a college degree. One of 10 children, he made good on that promise. And won the Heisman before he left.

But when he enrolled at Auburn, his speech misery was at its apex. Two of his sisters suffered from the same impediment. In Bo’s case, it was so bad that he would avoid announcers and reporters at all costs after games. He couldn’t even raise his hand in the classroom. He was a man-child who was terrified to talk.

To Auburn’s credit, the university pushed him to confront his fear head-on. They connected him with a linguistic therapist; that’s where the “Bo” self-reference was born. So it sounded a little silly, big deal. It obviated the stutter.

Auburn also pushed Bo to take a public speaking class — his worst nightmare. But he knuckled through it. In fact, he took it so seriously that he got up every morning at 5:30, stood in front of his bathroom mirror and interviewed himself holding his toothbrush for a microphone.

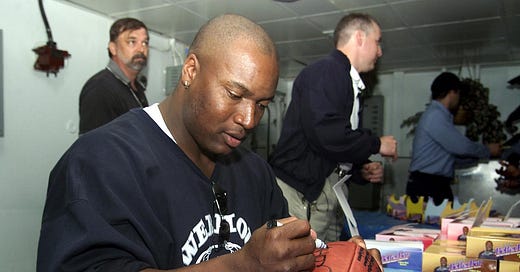

I happen to have a soft spot in my heart for Bo Jackson. The first time I ever brought a camera crew to a big league ball game, 34 years ago, happened during the time he was struggling to make his comeback from a hip injury for the Chicago White Sox. On that day, playing against his old Royal pals, Bo broke out. He drove in his first run in the first inning, and then in the fourth, with two men out, the Sox went on to score 10 runs. Bo drove in two of them — before shortstop Ozzie Guillen hit the first and only grand slam of his career.

I didn’t know about Bo Jackson’s battle with speech back then. In fact, in the media scrum in the Sox locker room after the game, he seemed as cocky talking as he was playing. He even made a self-deprecating joke about his performance compared to Guillen’s slam:

“I got to enjoy that two-run single for about two minutes. He spoiled it for me!”

Bo had a big ol’ smile on his face. And every reporter gathered around him laughed out loud.

Nearly 20 years later, Bo Jackson stood up in front of thousands of his fellow Tigers at an Auburn graduation ceremony, and spoke. And he gave advice that he, himself, had lived:

“Do like I did. Get outside of that box that you’ve grown accustomed to. Go places that you never thought you’d go. Meet people that you never thought you would get a chance to meet. Because that’s the only way you’re going to enjoy life. Get outside of the box. Make things happen. Be your own person.”

The place went nuts.

I think the ultimate irony of Bo Jackson’s early speech struggles is how his strategy of substituting “Bo” for “I” became so familiar in the consciousness of American sports fans that it inspired the “Bo Knows” campaign — which helped seal his folk hero status.

Talk about a classic lesson of turning weakness into strength.

Bo Knows was wonderful. And so was Bo.