RESPECT: Whose Opinions Matter?

"The funny thing is that after the 'original diva' went up to Hall, other artists started approaching each other and asking for their autographs. It wasn't just a love-fest — it was a respect-fest."

Editor’s Note: This column is one of 10 new pieces included in the anthology book STAYING ALIVE, set for release on Jan. 5. If you would like to receive a free E-Copy and keep getting all TGM content in 2025, SIGN UP for your discounted subscription!

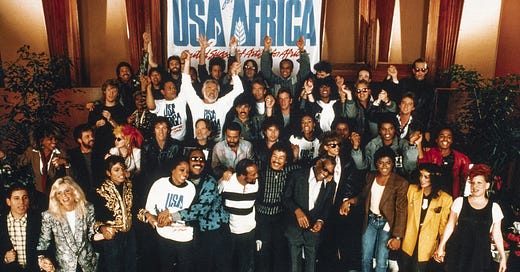

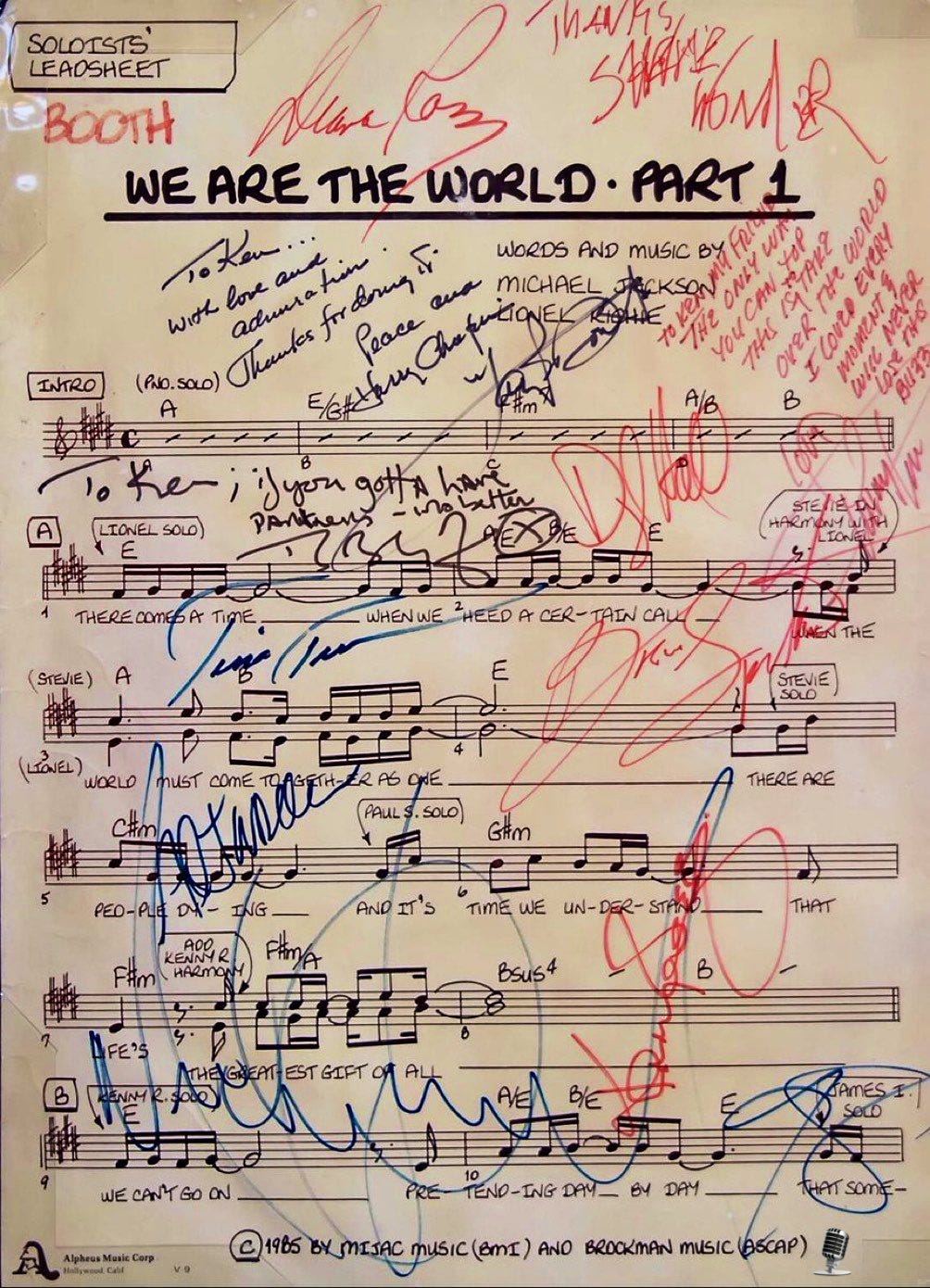

There’s a poignant and incredibly telling moment in the recent hit documentary The Greatest Night in Pop. During a break in the recording of the song “We Are the World” in 1985, Diana Ross walks up to Daryl Hall with her music sheets in hand and says:

“Daryl, I’m your biggest fan! Would you sign my music for me?”

That’s right. Diana Ross. Lead singer of the Supremes. Twelve No. 1 hits with them and another six on her own (“Baby Love” literally started playing in the coffee shop where I wrote this). Billboard’s “Female Entertainer of the Century.” Two stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. She wanted Daryl Hall’s autograph.

This is not to disparage Daryl Hall in any way, still a very popular live singer. But the stars and musical producers in that recording session could not help but notice that the original “diva” respected Hall enough to want a souvenir from him.

The funny thing is that after Ross went up to Hall, other artists started approaching each other and asking for their autographs. Picture Cyndi Lauper zipping over to Lionel Richie and Bruce Springsteen. The love-fest was on full display. But it was more than that — it was a respect-fest.

In fact, moments later in the film, Richie describes how everyone in the room felt about performing not only with, but up against one another:

“That circle was the intimidating circle of life. Quincy [Jones] was right: When it’s time for your part to sing, you are gonna give 200 percent because the class is looking at you. And to see everyone’s preparation and vulnerability was pretty amazing. You were on your game at that point.”

These artists have millions upon millions of fans. All of them. Stevie Wonder, Bob Dylan, Harry Belafonte, Smokey Robinson, Steve Perry, Billy Joel, Tina Turner, Willie Nelson… And they love their fans. Who wouldn’t? But there’s something different about hearing praise from the folks who know what it takes.

As I watched Michael Jackson’s central role on “We Are the World” and was thinking about the whole respect-among-peers thing, I remembered what he’d said decades ago in another doc about a phone call he received from Fred Astaire. It was the morning after Jackson’s world-shaking performance of “Billie Jean” at the “Motown at 25” celebration on NBC in 1983:

“Fred Astaire called my house and said, ‘I saw the show last night. I taped it. I watched it twice this morning. You’re a hell of a mover and you really put them on their A-S-S!’ And I said, ‘God, thank you. It’s so wonderful for you to say that, ’cause I think you’re the best.’”

These are very high-profile examples of this respect principle I’m speaking of — but it applies to just about every type of criticism or feedback that any of us get regarding something we care about.

If you’re a teacher, it’s likely that the input you receive from other teachers you respect will be far more important to you on a personal level than from some school board appointee. Are you a businessperson? A parent? An athlete? A nurse? A mechanic? A political figure? A painter? A writer? A plumber? Doesn’t it feel a little different when someone who’s been inside the belly of the best shares their informed opinion with you?

Criticism is a tricky concept. As human beings, we become conditioned to respond reactively toward criticism. It’s a function of our ego. And it’s easy to say, “Ah, screw all of the critics, my opinion is what matters.” Sure, our own opinions of our efforts matter a great deal. Usually most of all. But shutting out all other feedback, good or bad, isn’t healthy either. The key is to find that balance, The Golden Mean. And to always consider the source.

The first time I experienced this in a meaningful way was after I finished reporting a criminal justice series for local TV news many years ago. It was a pretty idealistic project, as it was designed to reform and improve the way the news covered crime. I even had to get a grant from outside my NBC station to fund the series and documentary. It took six months to complete, and at the time I was really proud of it.

I left that NBC station in California not long after the series. I didn’t want to go back to the same ol’ chasing mayhem after making such an impassioned plea against it. But I confess, there were moments when I wondered if there wasn’t a “holier than thou” overtone to the project. And I think that a few of my colleagues felt that way.

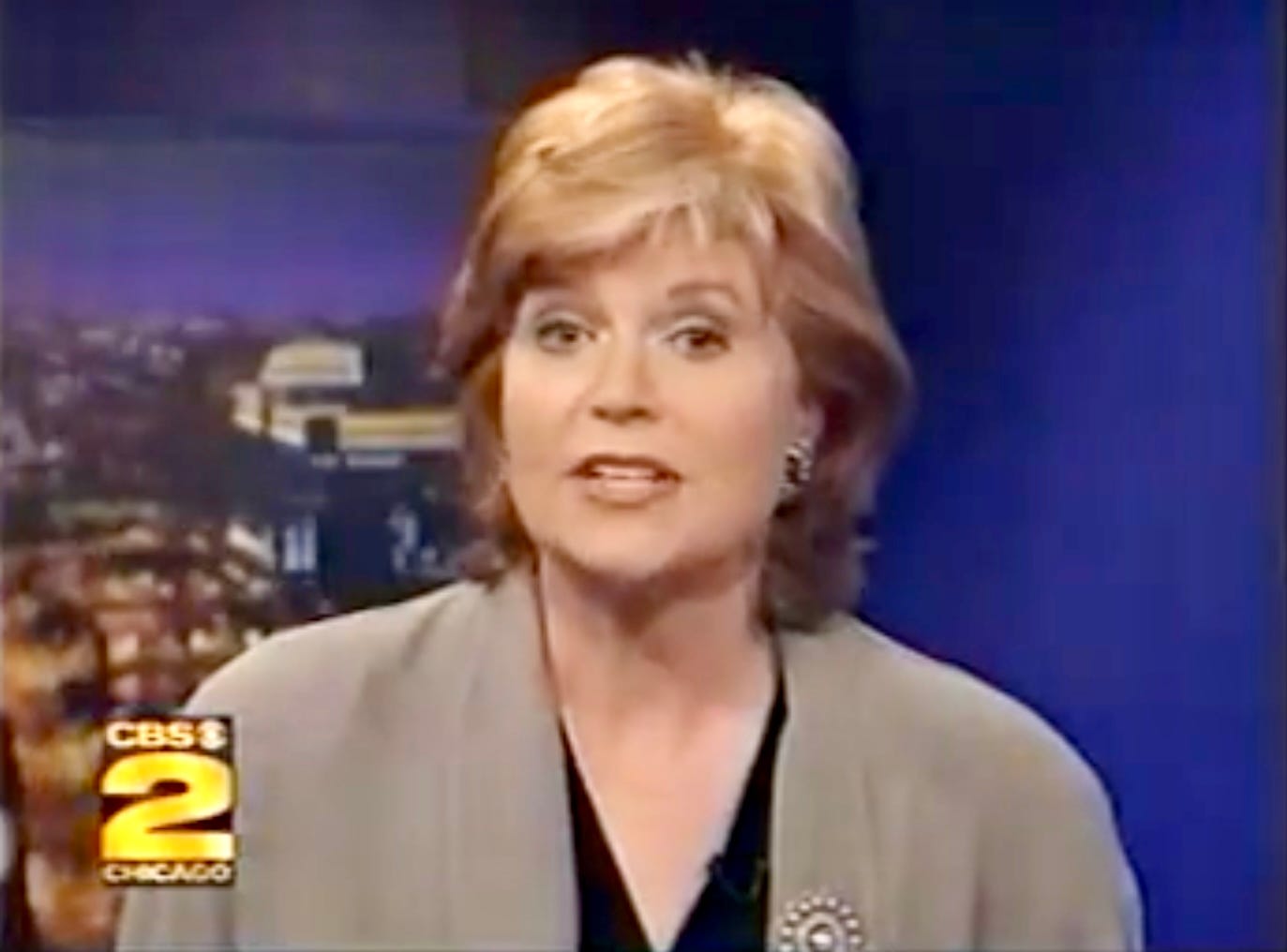

After I’d moved back home to Chicago, I reached out to a TV anchor there who was more like a local legend. Her name was Carol Marin, and she had recently undertaken an effort to totally revamp the CBS-TV affiliate’s news operation — gearing it almost exclusively to news that mattered, versus the happy crap or sensational stuff that most newscasts run.

To my surprise, Carol knew who I was and had read about my project in a journalism magazine called Brill’s Content. She immediately offered generous praise, and we talked about the constructive possibilities that still existed in television journalism. The entire conversation meant more to me than she will probably ever know.

Not only was Carol Marin a Peabody Award-winning journalist and a 60 Minutes correspondent, but she was someone who truly got what I was trying to do. Because of that, my respect for her was immense, and her opinion mattered greatly to me.

It wasn’t just because her observations were complimentary. Only a few years later, I had moved from straight news reporting to running political campaigns. Now Carol was on the other side of the table — or a phone line. She was the most knowledgeable and hard-hitting political journalist in the city, and we had our battles. One time, we were yelling and swearing off the record about what I felt was unfair coverage of one of my horses. Sure, I thought I was right, but my deep respect for her made me think twice. And our professional relationship only deepened as a result.

Years later, when I wrote my first book about reforming the U.S. Congress, Carol wrote a column in the Chicago Sun-Times that was incredibly generous. I knew right when I read it that the book had at least achieved a baseline level of gravitas.

We all have Carols in our lives. They need not be well known or have any pedigree. It’s our respect for them that commands our attention and consideration. Not to dwell on or to rest on — but to take into account when we’re trying to draw our own conclusions.